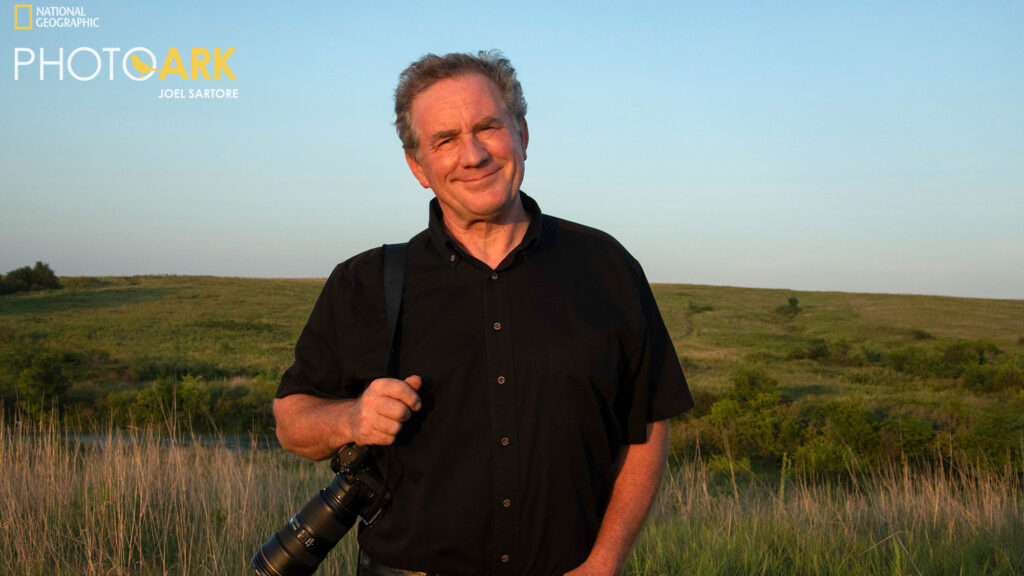

Eagle Scout Joel Sartore (1977) has devoted his life to saving animals and encouraging people to care about the Earth’s biodiversity. As a National Geographic Explorer and conservation photographer, he has authored numerous books and has contributed photographs to many others. He is also the founder of an ambitious project called the National Geographic Photo Ark that aims to document every animal in human care before the opportunity is lost forever.

Joel credits his parents and his years as a Scout with nurturing his interests in biodiversity and conservation. “My parents cared about nature. Being in Scouting was also a great way to experience and care about nature.”

While on a Scout camping trip in Nebraska, he remembers using a seine in a farm stream. The variety of fish caught that day was surprising. What was not surprising was when all the fish were put back.

“All that diversity of fishes running through a farmer’s field,” he marvels. “That was amazing to me. Between Scouting and hunting and fishing with my father, I experienced what nature had to offer in Nebraska. That stuck with me and led me to be a natural history photographer, a conservation photographer.”

Joel, a native of Ralston, Nebraska, earned his Eagle rank in 1977. “My parents taught me that I could be whatever I wanted. Being an Eagle Scout put me on the right path.

“When I meet other Eagle Scouts, we understand we’re brothers. I’m a Type A guy, driven to do more. Scouting is about setting goals and reaching them. I operate that way. The Scouts helped nourish that.”

Scouting teaches youth to solve problems, a skill that served Joel well. “Working as a National Geographic photographer, we’re on our own a lot. No one tells you to get up early to get sunrise pictures. Being in Scouts taught me to solve problems. I’m very proud of that. I’m proud of my family. I’m proud of the Photo Ark and the folks who choose to work with us. But being an Eagle Scout was fundamental.”

The true measure of a person, he believes, does not happen when times are easy. “The true measure is when times are tough. You will get knocked down. You have to get up again. How do you overcome adversity? These are critical things you learn in Scouting—that and being respectful, doing what you say you’ll do. Those are qualities that are sometimes lacking in the world now, along with civility.”

Following graduation from Ralston High School in 1980, he attended the University of Nebraska-Lincoln where he majored in journalism. He joined the Kansas newspaper The Wichita Eagle, and spent six years there, first as a photographer and then as Director of Photography. It was during his time in Wichita that he met photo legend James Stanfield who reviewed Joel’s work and encouraged him to send a portfolio of his photos to the National Geographic Society in Washington, D.C.

As with so many worthwhile endeavors in life, it took determination and persistence, but eventually, Joel was hired as a contract photographer for National Geographic Magazine. He explains that working for National Geographic requires more than being a skilled photographer or writer. National Geographic photojournalists must bring something extra to the job. Joel believes it was his perseverance that eventually got him his dream job.

“You can’t give up. Everybody faces setbacks. I also listened to what my bosses told me.”

A photojournalist’s work is challenging and potentially dangerous, requiring stamina and mental acuity. In Scouting, Joel learned to respect the outdoors and the importance of leaving a campsite as undisturbed as possible. When working with wildlife in a remote locale, it is even more important to take care. It is critical that a photojournalist respect the animals being photographed in their natural habitat. Invariably, human mistakes happen. Those mistakes can turn deadly.

(Story Continues after Photos…)

A Florida panther, Puma concolor coryi, at Lowry Park Zoo, Florida, 2012.

Photo by Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark.

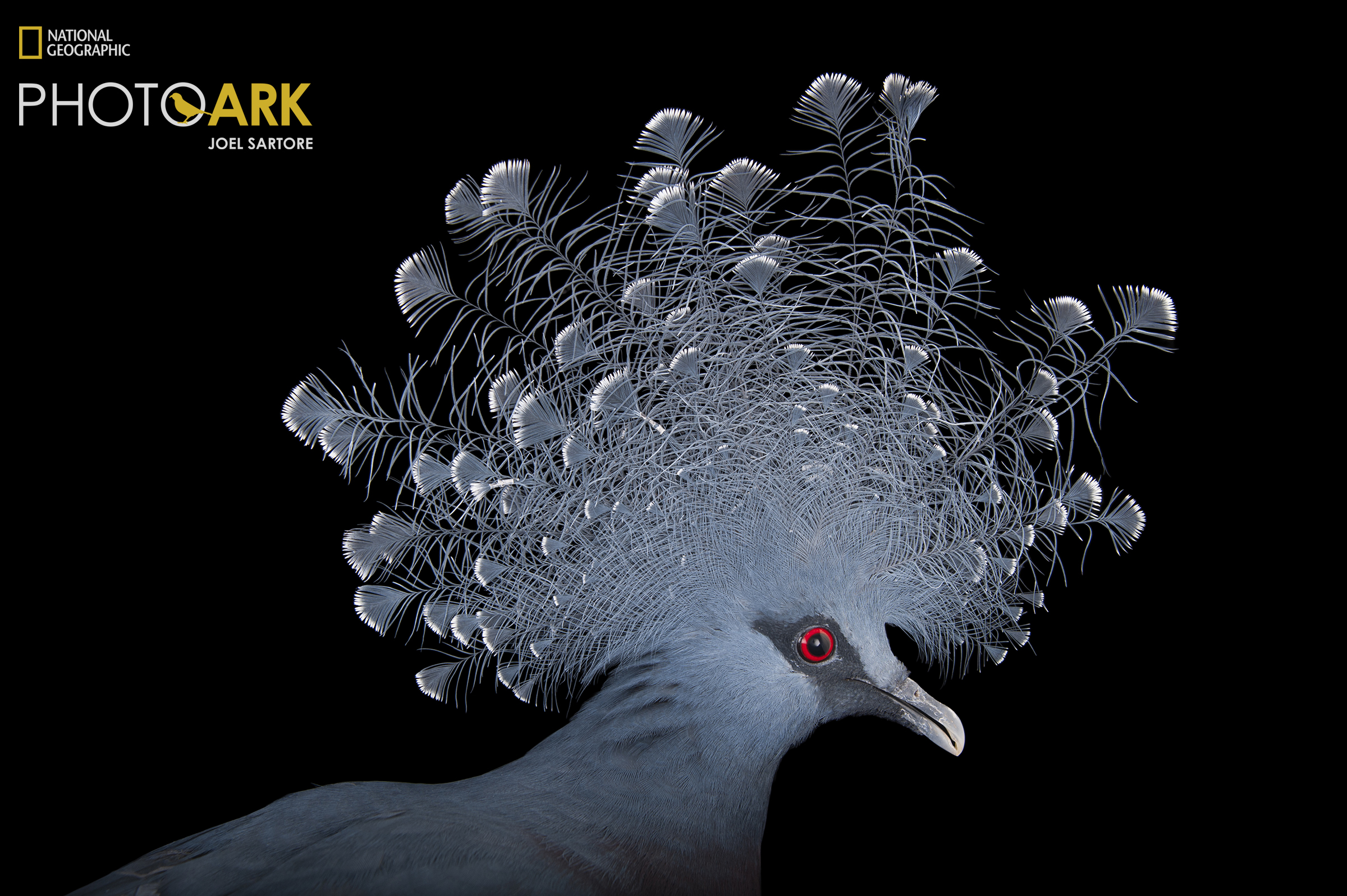

A Victoria crowned pigeon, Goura victoria, at the Columbus Zoo, Ohio, 2012.

Photo by Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark.

Orange spotted filefish, Oxymonacanthus longirostris, at Omaha’s Henry Doorly Zoo and Aquarium, Nebraska, 2013.

Photo by Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark.

A springbok mantis, Miomantis caffra, at Auckland Zoo, New Zealand, 2013.

Photo by Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark.

A Sierra Nevada ensatina salamander, Ensatina eschscholtzi platensis, at San Francisco State University, California, 2008.

Photo by Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark.

A ribboned pipefish, Haliichthys taeniophorus, at Dallas World Aquarium, Texas, 2013.

Photo by Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark.

A koala, Phascolarctos cinereus, with her babies at Australia Zoo Wildlife Hospital, 2011.

Photo by Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark.

Red eyed tree frog, Agalychnis callidryas, photographed in Seattle, Washington, 2011.

Photo by Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark.

An endangered baby Bornean orangutan, Pongo pygmaeus, with her adoptive mother, a Bornean/Sumatran cross, Pongo pygmaeus x abelii, at the Houston Zoo, Texas, 2013.

Photo by Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark.

An octopus, Octopoda, at Dallas World Aquarium, Texas, 2013.

Photo by Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark.

A Saint Vincent parrot, Amazona guildingii, at the Houston Zoo, Texas, 2015.

Photo by Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark.

An African leopard, Panthera pardus pardus, at the Houston Zoo, Texas, 2011.

Photo by Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark.

A bobtail squid, Euprymna scolopes, at Monterey Bay Aquarium, 2014.

Photo by Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark.

An African slender snouted crocodile, Ouroborus cataphractus photographed in Tampa, Florida, 2012.

Photo by Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark.

Joel Sartore carefully photographs a dwarf caiman, Paleosuchus palpebrosus, at the Sunset Zoo, 2011.

Photo by Cole Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark.

Joel has faced his own mortality more than once. He has been chased by grizzlies and found spitting cobras in his camera gear. “A lot happens in the field for National Geographic,” he says. “Everybody wants to know if I’ve been attacked by a big animal. If you are, you did something wrong. Nine times out of ten, it’s the little stuff that gets you, like insect born illnesses.”

In fact, Joel was bitten by a female Phlebotomus Sand Fly carrying leishmaniasis, a microscopic flesh-eating parasite. When he noticed a hole on his leg that wouldn’t heal, he spent an arduous month on chemotherapy.

One of the worst job-related events he experienced was exposure to a hemorrhagic disease called Marburg Virus after going into a bat cave in Uganda. Hot bat guano landed in his eye. He had to be quarantined for three weeks and considers himself lucky that he did not get the deadly virus.

On another trip, he and his native guide heard a swarm of killer bees. “We dove under the car and stayed very still. It sounded like a train coming. Fortunately, the bees kept going.”

In 2005, Joel’s personal life took a hard turn when his wife, Kathy, was diagnosed with breast cancer. Joel stayed home to care for his wife and their three children: Cole, Spencer, and Ellen.

Kathy recovered, but her illness led Joel to further examine the fragility and brevity of life—a point he understood from his work photographing endangered species. But now, the question took on heightened significance.

“That time at home taught me the value of paying attention. Most animals in trouble are very small. They are little critters who live high up in a tree or in the mud. It was something I got to think about. How will we ever know they exist? Many haven’t been documented.”

This led him to start the Photo Ark in 2006, a photo archive of global biodiversity, made possible by a grant from the National Geographic Society. He envisioned a series of close-up portraits of animals that would avoid distractions and ultimately help people make eye contact with an animal. He says black-and-white backgrounds level the playing field, eliminating size comparisons. In these portraits, a mouse is every bit as large and special as an elephant.

The success of the Photo Ark has led Joel to become a popular keynote speaker. Forbes Magazine calls him a “social star” with 1.6 million social media followers. He has visited 60 to 70 countries but tends to visit the same places, such as Brazil and Indonesia, because they are biologically diverse. “We call them biodiversity hot spots,” he says.

He believes that every species is important to the Earth’s survival. We know that bees and even flies pollinate fruits and vegetables. An intact rainforest regulates the amount of rainfall in areas where crops are grown. Every living being is interconnected.

“But beyond what’s in it for us, I believe that each species has a basic right to exist,” he says.

There are about 20,000 to 22,000 animal species in human care around the world. Joel has made portraits of more than 13,500 of them over the past16 years. He is determined to keep going until he has them all, some 10 to 15 years from now. His son, Cole, an Eagle Scout since 2011 and a fine art appraiser, accompanies Joel on shoots to help with lighting.

“He can carry on if I can’t,” Joel says.

Every purchase from the Photo Ark Store goes directly to support the organization’s mission: getting the public to care and helping to protect species from extinction. For more information, go to www.joelsartore.com or natgeophotoark.org.